The US liquidity monetary policies have created a dangerous paradox

A paradox has emerged in the financial markets of the advanced economies since the 2008 global financial crisis. Unconventional monetary policies have created a massive overhang of liquidity. But a series of recent shocks suggests that macro liquidity has become linked with severe market illiquidity.

Policy interest rates are near zero (and sometimes below it) in most advanced economies, and the monetary base (money created by central banks in the form of cash and liquid commercial-bank reserves) has soared – doubling, tripling, and, in the US, quadrupling relative to the pre-crisis period. This has kept short- and long-term interest rates low (and even negative in some cases, such as Europe and Japan), reduced the volatility of bond markets, and lifted many asset prices (including equities, real estate, and fixed-income private- and public-sector bonds).

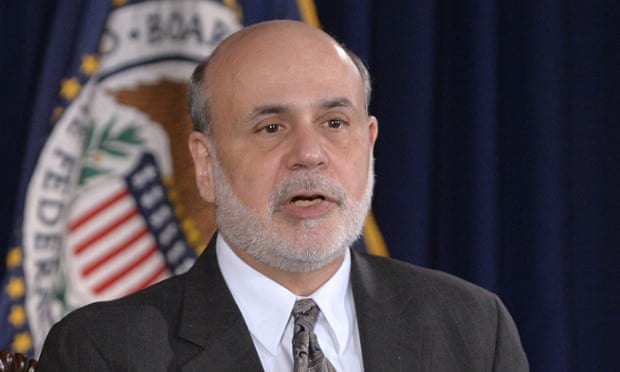

And yet investors have reason to be concerned. Their fears started with the “flash crash” of May 2010, when, in a matter of 30 minutes, major US stock indices fell by almost 10%, before recovering rapidly. Then came the “taper tantrum” in the spring of 2013, when US long-term interest rates shot up by 100 basis points after then-Fed chairman Ben Bernanke hinted at an end to the Fed’s monthly purchases of long-term securities.

Likewise, in October 2014, US treasury yields plummeted by almost 40 basis points in minutes, which statisticians argue should occur only once in 3bn years. The latest episode came just last month, when, in the space of a few days, 10-year German bond yields went from five basis points to almost 80.

These events have fueled fears that, even very deep and liquid markets – such as US stocks and government bonds in the US and Germany – may not be liquid enough. So what accounts for the combination of macro liquidity and market liquidity?

For starters, in equity markets, high-frequency traders (HFTs), who use algorithmic computer programs to follow market trends, account for a larger share of transactions. This creates, no surprise, herding behavior. Indeed, trading in the US nowadays is concentrated at the beginning and the last hour of the trading day, when HFTs are most active; for the rest of the day, markets are liquid, with few transactions.

A second cause lies in the fact that fixed-income assets – such as government, corporate, and emerging-market bonds – are not traded in more liquid exchanges, as stocks are. Instead, they are traded mostly over the counter in illiquid markets.

Third, not only is fixed income more liquid, but now most of these instruments – which have grown enormously in number, owing to the mushrooming issuance of private and public debts before and after the financial crisis – are held in open-ended funds that allow investors to exit overnight. Imagine a bank that invests in illiquid assets but allows depositors to redeem their cash overnight: if a run on these funds occurs, the need to sell the illiquid assets can push their price very low very fast, in what is effectively a fire sale.

Fourth, before the 2008 crisis, banks were market makers in fixed-income instruments. They held large inventories of these assets, thus providing liquidity and smoothing excess price volatility. But, with new regulations punishing such trading (via higher capital charges), banks and other financial institutions have reduced their market-making activity. So, in times of surprise that move bond prices and yields, the banks are not present to act as stabilizers.

In short, though central banks’ creation of macro liquidity may keep bond yields low and reduce volatility, it has also led to crowded trades (herding on market trends, exacerbated by HFTs) and more investment in illiquid bond funds, while tighter regulation means that market makers are missing in action.

As a result, when surprises occur – for example, the Fed signals an earlier-than-expected exit from zero interest rates, oil prices spike, or euro-zone growth starts to pick up – the re-rating of stocks and especially bonds can be abrupt and dramatic: everyone caught in the same crowded trades needs to get out fast. Herding in the opposite direction occurs, but, because many investments are in illiquid funds and the traditional market makers who smoothed volatility are nowhere to be found, the sellers are forced into fire sales.

This combination of macro liquidity and market illiquidity is a time-bomb. So far, it has led only to volatile flash crashes and sudden changes in bond yields and stock prices. But, over time, the longer central banks create liquidity to suppress short-run volatility, the more they will feed price bubbles in equity, bond, and other asset markets. As more investors pile into overvalued, increasingly illiquid assets – such as bonds – the risk of a long-term crash increases.

This is the paradoxical result of the policy response to the financial crisis. Macro liquidity is feeding booms and bubbles; but market illiquidity will eventually trigger a bust and collapse.

//

Federal Open Market Committee

///

DEFINITION of 'Monetary Policy'

The actions of a central bank, currency board or other regulatory committee that determine the size and rate of growth of the money supply, which in turn affects interest rates. Monetary policy is maintained through actions such as modifying the interest rate, buying or selling government bonds, and changing the amount of money banks are required to keep in the vault (bank reserves).The Federal Reserve is in charge of the United States' monetary policy.

BREAKING DOWN 'Monetary Policy'

Broadly, there are two types of monetary policy, expansionary and contractionary. Expansionary monetary policy increases the money supply in order to lower unemployment, boost private-sector borrowing and consumer spending, and stimulate economic growth. Often referred to as "easy monetary policy," this description applies to many central banks since the 2008 financial crisis, as interest rates have been low and in many cases near zero.Contradictory monetary policy slows the rate of growth in the money supply or outright decreases the money supply in order to control inflation; while sometimes necessary, contractionary monetary policy can slow economic growth, increase unemployment and depress borrowing and spending by consumers and businesses. An example would be the Federal Reserve's intervention in the early 1980s: in order to curb inflation of nearly 15%, the Fed raised its benchmark interest rate to 20%. This hike resulted in a recession, but did keep spiraling inflation in check.

Central banks use a number of tools to shape monetary policy. Open market operations directly affect the money supply through buying short-term government bonds (to expand money supply) or selling them (to contract it). Benchmark interest rates, such as the LIBOR and the Fed funds rate, affect the demand for money by raising or lowering the cost to borrow—in essence, money's price. When borrowing is cheap, firms will take on more debt to invest in hiring and expansion; consumers will make larger, long-term purchases with cheap credit; and savers will have more incentive to invest their money in stocks or other assets, rather than earn very little—and perhaps lose money in real terms—through savings accounts. Policy makers also manage risk in the banking system by mandating the reserves that banks must keep on hand. Higher reserve requirements put a damper on lending and rein in inflation.

In recent years, unconventional monetary policy has become more common. This category includes quantitative easing, the purchase of varying financial assets from commercial banks. In the US, the Fed loaded its balance sheet with trillions of dollars in Treasury notes and mortgage-backed securities between 2008 and 2013. The Bank of England, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan have pursued similar policies. The effect of quantitative easing is to raise the price of securities, therefore lowering their yields, as well as to increase total money supply. Credit easing is a related unconventional monetary policy tool, involving the purchase of private-sector assets to boost liquidity. Finally, signaling is the use of public communication to ease markets' worries about policy changes: for example, a promise not to raise interest rates for a given number of quarters.

Central banks are often, at least in theory, independent from other policy makers. This is the case with the Federal Reserve and Congress, reflecting the separation of monetary policy from fiscal policy. The latter refers to taxes and government borrowing and spending.

The Federal Reserve has what is commonly referred to as a "dual mandate": to achieve maximum employment (in practice, around 5% unemployment) and stable prices (2-3% inflation). In addition, it aims to keep long-term interest rates relatively low, and since 2009 has served as a bank regulator. Its core role is to be the lender of last resort, providing banks with liquidity in order to prevent the the bank failures and panics that plagued the US economy prior to the Fed's establishment in 1913. In this role, it lends to eligible banks at the so-called discount rate, which in turn influences the Federal funds rate (the rate at which banks lend to each other) and interest rates on everything from savings accounts to student loans, mortgages and corporate bonds.

//

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jun/01/the-liquidity-timebomb-fiscal-policies-have-created-a-dangerous-paradox

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomc.htm

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/default.htm

Comments

Post a Comment